It is very common for an arthritic knee to become crooked. This deformity may even progressively worsen over time. Not only can knee replacement surgery potentially eliminate the pain caused by knee arthritis, it should correct or improve a crooked knee deformity as well.

Knee arthritis results in the cartilage on the bone ends (‘hyaline’ articular cartilage) becoming thinned and cracked. Additionally, there are two structures of fibro-cartilage (meniscus) that are vulnerable to tearing. These are crescent shaped structures lining the edge of the tibia (shin bone) which deepen at the bottom half of the joint and are slightly mobile. They can undergo deterioration during the arthritic process, becoming shredded and frayed, resulting in obstruction to the joint. If parts of the meniscus or articular cartilage break off, loose bodies can occur within the joint as well.

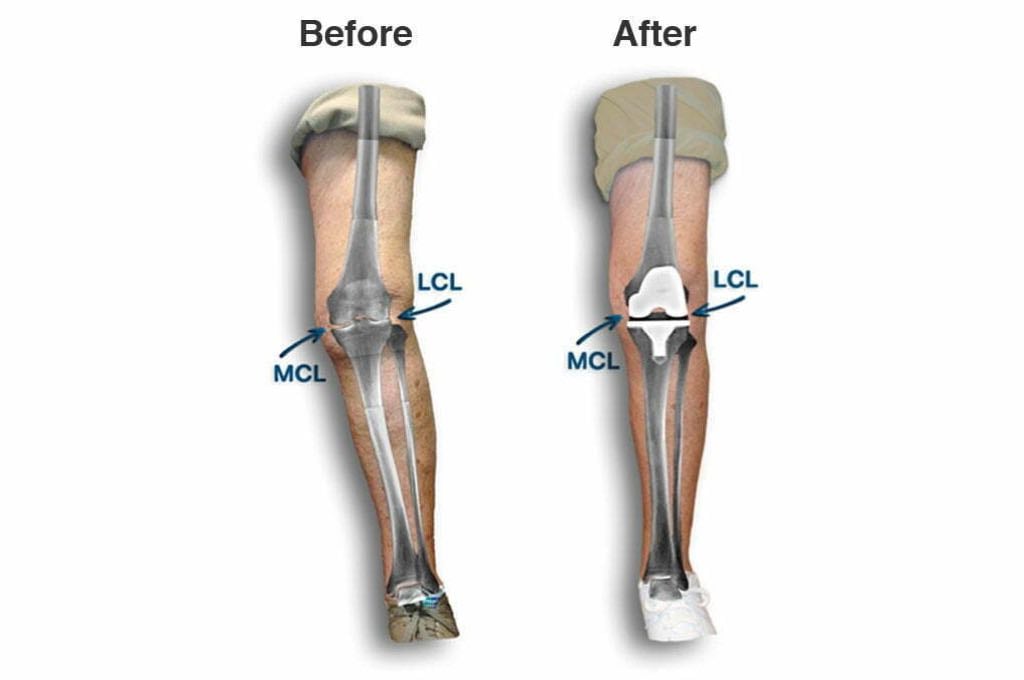

Over time, as the arthritis worsens the joint space becomes narrowed when viewed on an x-ray. Once the narrowing becomes significant, bone on bone contact may ensue, causing discomfort and pain. The cartilage and bone loss can also result in knocked kneed (valgus) or bow legged (varus) deformities which can vary from mild to extreme.

This kind of deformity is often entirely corrected – or at least reduced – as a result of total knee replacement.

Such deformities will be corrected during the routine steps of a knee replacement. The surgeon will remove the damaged bone using traditional guides and jigs, custom made cutting blocks or may even utilize computer-assisted guidance.

When the knee bones are correctly aligned, your surgeon will evaluate the ligaments. In Jessica’s knee, the ligament on the outside of the knee (LCL) needed to be fractionally lengthened to provide the proper space for the newly created bone cuts. If this contracted ligament were not corrected, the outside of the knee would have remained too tight. This crucial step is called “balancing” the knee. Some knees require very little balancing. However, in cases of significant deformity, the knee may need extensive balancing.

After these steps, your orthopaedic surgeon will implant the new knee prosthesis. This knee replacement should provide many years of improved function and maintain the corrected leg alignment.