A comprehensive guide to improving scar management

As BoneSmarties, we want you to love your scar. It’s your Badge of Courage. For many, your surgical scar represents the challenges you faced and conquered in recovery. It shows you took action to reclaim your life from arthritis and that you’re beginning to resume your normal lifestyle again.

Having joint replacement surgery means you will eventually have a scar. Knowledge of how a wound heals coupled with information about what things you can do to improve or minimize the appearance of your healing incision is the path that will lead you to minimizing your scar.

Scars result from any serious wound or surgery, so what’s different now?

There has been no shortage of studies and clinical data surrounding scar management over many decades. Recently, efforts have been made to transfer some of the basic science of healing into more understandable and usable formats. In addition, there is a much greater base of knowledge than ever before regarding stem cells and cellular responses that explains the mechanics of wound healing. And, of course, the internet provides the perfect vehicle for any patient to have easy access to information. Because most patients and professionals in the medical field have limited time to spend sifting through the mind-boggling volume of information (both good and bad) available today, BoneSmart is providing this guide to give you pertinent data in an easily understandable format.

Factors contributing to scar formation. Creation of a scar is part of the wound healing process. There are some factors such as age, ethnicity and previous history of hypertrophic or keloid scar development that cannot be changed. But there are other factors that can make a difference and it’s important to know and understand how your body may respond to various circumstances during your healing process. Proper management of a scar can extend up to a year following surgery. Quick intervention to any abnormal growth is key to preventing an unsightly scar.

The healing process

The body is a complex and remarkable machine, and the dynamic process of wound healing is a great example of how our body’s different systems, along with the proper wound care products, work together to repair and replace devitalized tissues.

But how, exactly, does our body heal?

Wound healing is an intricate process that can be divided into four distinct stages.

- Hemostasis (blood clotting). Within the first few minutes following the conclusion of your surgery, platelets begin to bind together within the wound to plug any breaks in blood vessels, slowing and preventing further bleeding.

- Inflammation. During this phase, white blood cells and other specialized cells work to clear damaged and dead cells along with any bacteria or debris. This is your body’s normal immune system response to injury and other harmful things entering your body. This phase can last anywhere from four to six days up to several weeks and is often associated with symptoms typically associated with inflammation: pain, warmth, swelling and redness in the wound area.

- Proliferation (growth of new tissue). In this phase, the wound goes through three distinct stages. During the first stage, shiny, deep red granulation tissue fills the wound bed with connective tissue, and new blood vessels are formed. Then, during contraction, the wound margins contract and pull toward the center of the wound. In the third stage, epithelial cells arise from the wound bed or margins and begin to migrate across the wound bed in leapfrog fashion until the wound is covered with epithelium. The Proliferation phase generally lasts from 4-24 days.

- Maturation (remodeling). During maturation and remodeling, the new tissue slowly regains strength and flexibility. Collagen fibers reorganize and realign along tension lines and become cross-linked to increase the strength. The collagen will reach approximately 20% of its tensile strength after 3 weeks, increasing to 80% by 12th week. The maximum scar strength is 80% of that of unwounded skin. As this process continues, cells that are no longer needed die as part of the body’s normal process of cellular regeneration. The entire remodeling phase can last anywhere from 21 days to two years.

As remarkable and complex as the healing process is, it can be susceptible to interruption due to many factors including excessive moisture, infection, age, new trauma to the wound, nutritional status, and body type. If the right healing environment is established, the body works in wondrous ways to heal and replace injured tissue.

The science of the healing process

When tissue is cut and then sutured back together following surgery, blood begins to form a clot in the wound. The part of the clot closest to the skin surface dries out to form a scab while the lower part is the setting for many of the key processes of wound healing. But the actual development of a scar is not immediate.

Scars form after a wound has gone through the process described below and healing is complete.

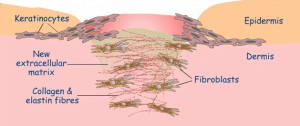

At the beginning of the healing process, different types of cells are produced to perform a variety of functions. Keratinocytes are cells closest to the surface of the skin, the epidermis. As keratinocytes grow and are pushed upward toward the surface, they form a layer that helps protect a wound against microbial, viral, fungal and parasitic invasion. They also deflect UV radiation and minimize heat and water loss. Meanwhile, in the dermal layer of the skin, the body immediately starts forming new collagen fibers (a naturally occurring protein in the body) to mend damage from the incision. Cells called fibroblasts move in from surrounding tissue, begin to dissolve the blood clot and intertwine with the new collagen fibers. The mesh of fibroblasts and collagen are part of a new extracellular matrix that makes up the newly healed area in the dermal skin layer. Some fibroblasts become specialized myofibroblasts and contract the wound to reduce the size of damaged tissue. This occurs when the myofibroblasts grip the wound edges and contract, using a mechanism resembling that in smooth muscle cells. The new collagen and fibroblast extracellular matrix form the basis of the scar.

As healing progresses and the mesh of cells forming the extracellular matrix increase, collagen begins to fill in the gaps around and under the wound scab, forming new skin. This tissue has a different texture and quality than the surrounding tissue. It has no fat cells or hair follicles and is the beginning of your scar. Collagen production stops after a few weeks and capillaries form to deliver blood to the injured area, helping healing to progress. During this time, the external incision may appear red, raised and lumpy.

Your scar will never be quite as strong as the original skin. In time, some collagen breaks down at the site of the wound and the blood supply reduces. The scar gradually becomes smoother, softer and paler. Although scars are permanent, they can fade over a period of up to two years.

Scar facts

- Any injury that extends below the outer surface of the skin will likely form a scar.

- The deeper the wound, the deeper the scar and the longer the healing process will take. Surgical incisions that cut the tissue below the outer skin layers usually take longer to heal than a skinned knee from a fall on the sidewalk.

- When the edges of the wound touch each other, skin cells can migrate and close over the wound in a day or two. When the sides of the wound aren’t touching, it takes longer. This is why a surgeon’s skill at wound closure is important.

- Taut skin is more resilient than skin that has lost its elasticity with age. The more resilient your skin, the faster your scar is likely to heal.

Most scars become flat and pale eventually. However, when the body produces too much collagen, scars can be raised. Raised scars are called hypertrophic scars or keloid scars.

Scar management: What to expect when healing

All of us want to have the best healing experience possible and there are things you can do to prevent problems that would hinder recovery. While your incision is healing, it is important not to overdo your activity or therapy. Even though you may have been sent home from the hospital quickly, you must remember your body has not healed completely. You were sent home TO heal and recover. Pay attention to how your body responds to therapy, activity or exercise. If you have pain or swelling at the incision or below it, scale back your activity. Rest and ice the area until things improve. There is no rush and this is not the time to push yourself or try to build muscle strength. Your body only has so much energy to devote to healing and activity, so you want to allow as much as possible to go toward wound healing in the first critical months.

The type of skin that regenerates over a small, superficial cut is filled with fat cells called adipocytes which means the new repair cells will eventually blend into your normal skin perfectly once the wound has healed. A surgical incision is quite different as it goes much deeper, impacting multiple levels of tissue. The unique wound healing process following surgery will create scar tissue that ultimately can have an appearance that ranges from a small, thin white line to a bumpy, dark-colored keloid scar.

Scar tissue is made up almost entirely of cells called fibroblasts and doesn’t contain any fat cells or hair follicles. So instead of blending into the surrounding skin once the wound has healed, it will look different permanently. But in most cases, the difference can be improved and lessened with good wound management.

Here are some examples of what your incision may look like at the various stages of healing. These photos are of a right total hip replacement (RTHR), but you can expect similar results with a total knee replacement (TKR).

There are some general tips you should observe when caring for healing wounds that are likely to scar.

- Keep the wound clean and well-dressed. Your surgeon will tell you when it’s okay to remove certain dressings and will likely tell you how to clean the area. Never remove surgical dressings before your surgeon tells you it is okay. When you do change the dressing, wash your hands first and use disposable gloves.

- Don’t mess with it. In other words, no picking or scratching at scabs. The more you interfere with your body’s healing, the greater the risk for infections or other complications.

- Keep your wound dry until it’s completely closed. Don’t attempt any activity (including a bath) where you are completely submerged in water. Public swimming pools, hot tubs, lakes and the ocean are not recommended for at least a couple of months following surgery to avoid all risk for infection.

- Hypochlorous Solution (HOCL) is “Nature’s Germ Warrior!” Put it to work for you. You can use HOCL from the very first moment your incision is exposed following surgery, such as when you make a dressing change. This compound is the substance your own body generates to kill germs and encourage healing when it is wounded. During the complex and fragile process of healing, the more things you can do to maintain a clean and protected wound environment, the better the opportunity you have for faster healing. Establish a daily routine of applying Hypochlorous Solution as soon as possible after surgery. With its strong anti-bacterial properties, HOCL creates a positive healing environment. Less inflammation can translate into faster and better healing and less scarring.

In situations where your surgeon elects to use a special antimicrobial dressing, you may need to delay the use of hypochlorous solution until the dressing is removed (usually 10-14 days after surgery). For decades studies have consistently shown this compound to have almost miraculous capabilities for killing bacteria and viruses virtually on contact. In addition to its germ fighting capabilities, hypochlorous reduces inflammation and encourages the type of cell regeneration that can speed healing dramatically.

- Use only surgeon approved antibiotic creams. Note the words “surgeon approved.” After a wound has closed, consult your doctor before using any cream or ointment. Never use an antibiotic cream on a wound that is still bleeding.

Abnormal scar development

Some people have a tendency to develop scars that do not become smooth and pale with time because their bodies produce an excess of collagen. These are called keloid or hypertrophic scars. Both are more common in younger patients and dark-skinned individuals.

Keloid scars

Keloid scars

A keloid scar is an overgrowth of tissue that occurs when too much collagen is produced at the site of the wound. The scar keeps growing, even after the wound has healed. Keloid scars are raised above the skin. They are red or purple when newly formed and gradually become a little lighter. They can be itchy or painful and can restrict movement if they’re tight and near a joint. They grow outside the borders of the original wound.

Hypertrophic scars

Hypertrophic scars

Like keloid scars, hypertrophic scars are the result of excess collagen being produced at the site of a wound. But not as much collagen is produced in hypertrophic scars compared with the keloids. And while they do not grow beyond the boundary of the original wound, hypertrophic scars may continue to thicken for up to six months. Early intervention once a hypertrophic scar begins to develop is essential. A hypertrophic scar that does not improve by 6 months is a keloid and it should be aggressively managed with treatments such as steroid injections.

Some Do’s and Don’ts for good wound management

Nutrition and health. Not surprisingly, eating right can play a positive role in making sure your wound heals as quickly and cleanly as possible. Likewise, a healthy lifestyle also aids healing. Here are several factors of good nutrition and health that can influence your scar’s healing time.

Nutrition and health. Not surprisingly, eating right can play a positive role in making sure your wound heals as quickly and cleanly as possible. Likewise, a healthy lifestyle also aids healing. Here are several factors of good nutrition and health that can influence your scar’s healing time.

- Fresh fruits and vegetables eaten daily will supply your body with nutrients essential to wound healing such as vitamin A, copper and zinc.

- Foods rich in vitamin C help produce collagen.

- Getting extra protein will ensure your body has the energy it needs to heal and recover from surgery.

- Drinking plenty of fluids keeps the body hydrated and your skin moist for optimized healing.

- The body does its best healing during REM sleep. Although this deep sleep can be elusive during the early weeks of recovery, pay attention when your body is tired during the day and add in naps to make up for any sleep loss at night.

- Stress slows down the healing process, so try and keep stress to a minimum.

- High blood pressure, poorly controlled diabetes and circulatory conditions slow down healing. If you have these conditions, talk with your primary doctor BEFORE surgery to get blood pressure and sugars in line. Continue to keep your blood pressure and sugars in control during recovery. Post-surgery, gentle massage can help improve poor circulation.

Exposure to sunlight. You may have heard that you need to keep your new incision out of the sun and thought this was so you didn’t burn the fragile skin. While it’s true that the new skin may burn more easily, there are other reasons to avoid direct sunlight on your wound in the first couple of months of recovery. Sunlight is one of the last things your body needs as it tries to remodel scar collagen and mend a wound. The UV light can increase inflammation and free radical formation plus it may disrupt the body’s ability to create new collagen for repair. Use sunscreen and keep your wound out of the sun for at least 3 months.

Nicotine and smoking. Smoking can disrupt scar recovery. Nicotine makes blood vessels constrict, minimizing blood and oxygen flow to the wound as well as the rest of the body. In order for a wound to heal in the best way possible, it needs maximum blood supply and maximum oxygen. So do your whole body a favor and take this opportunity to stop smoking!